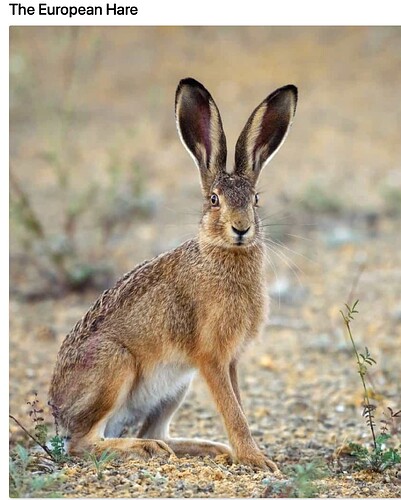

to minimise the need to address ear compatibility I suggest the European Hare

Top contributor

· ponreSsdtomAl5 r5i5c24g ttf 2f28h2 70cucum5M6m22:a53Pc9017pl ·

In 1927, Professor Thomas Parnell wanted to show his physics students a simple truth:

Some things that look solid… aren’t.

So, he began an experiment that would outlive him—and most of his students.

He poured a thick, black substance called pitch into a glass funnel. It looked like a rock. But pitch is a liquid—just an incredibly slow one.

He waited three years for it to settle. Then, in 1930, he cut the tip of the funnel.

And waited.

It took eight years for the first drop to fall.

And every drop since has taken about a decade to follow.

To date, only nine drops have fallen. That’s it.

It’s called the Pitch Drop Experiment, and it’s still going today at the University of Queensland in Australia.

It holds the Guinness World Record for the longest-running laboratory experiment in history. And it’s taught us that pitch is 230 billion times thicker than water.

Scientists tried filming the eighth drop with a webcam.

The camera glitched. The drop fell… unseen.

Even now, the setup remains—quiet, undramatic, but still moving.

And maybe that’s the point.

That in a world of instant everything, there’s beauty in patience.

That science isn’t always explosions—it’s also the hush of time passing.

And that even the slowest things… still move.

Ha! That reminds me that nearly 20 years ago, I asked @Bomb_Doe if he was a Pitch Drop Professor.

So Pitch drop gets a mention every 20 years on Blitz, which is half the rate of the pitch drops themselves.

Did I respond?

I think you denied it.

yep, that makes sense - I didn’t make professor until 2011. Plus while I’ve dabble in many things… pitch drops ain’t one of them.

Outstanding experiment though.

Everything flows. Have you seen those glass windows at Churches in Europe, where they are thicker at the bottom, same as Pitch Drop, but even slower.

Myth.

No, old windows typically do not become noticeably thicker at the bottom due to glass flowing like a liquid over time. The myth that old windows sag or become thicker at the bottom is inaccurate. While some older windows might appear to be thicker at the bottom, this is usually due to inconsistencies in the manufacturing process, not the flow of glass.

In other words the glass was taken out of the moulds too soon, before it had properly solidified.

Dingo? Bingo.

Domestic/wild dogs don’t seem to last long in the wild.

The Economist.

Australia’s dingoes are becoming a distinct species

Many will still be culled under false pretences

Not going to the dogsPhotograph: Getty Images

Apr 23rd 2025|Townsville, Queensland

Until very recently, it was assumed that Australian canines came in three varieties. There were native dingoes roaming the bush, distant cousins of dogs that arrived from Asia thousands of years ago. Then came domestic dogs, introduced in recent centuries by European travellers. Last were mongrel descendants of escaped pets and native dingoes.

Views on domestic dogs are straightforward: good as pets, but a threat when feral. Dingoes are more divisive. Many farmers see them as a threat to livestock and want them culled. But others are protective of this native animal, which is culturally important for Aboriginal people and helps balance the continent’s ecosystems.

Dingo-dog mixes, however, are an easier target for everyone. Still a menace to sheep, but also a conservation threat to the native dingoes, they can be culled without much controversy. Such culls often target “wild dogs”, a catch-all category which includes dingoes, feral dogs and mixes, but in areas closer to humans where no true dingoes were thought to live. However, new genetic-testing techniques have caused a stir by suggesting that dingo-dog hybrids are vanishingly rare. The majority of Australian canines being culled are, therefore, pure-bred dingoes.

The turning-point came with a paper published in Molecular Ecology in 2023 by Kylie Cairns at the University of New South Wales. She and her team compared the genomes of 391 wild and captive “dingoes” from across Australia—some expected to be native, others mixed—with genomes of 152 domestic dogs. This was done by zeroing in on 195,474 points in their genetic code where the two groups might be expected to have different DNA. The results showed that 70% of the wild dingoes sampled had no dog ancestry. What’s more, no feral dogs nor first-generation dingo-dog hybrids were identified. “It gave us a different picture than we were expecting,” Dr Cairns says.

A further round of DNA analysis, published in Evolution Letters in October, suggests the paper from 2023 may, if anything, have underestimated the level of dingo purity. This study, led by Andrew Weeks at the University of Melbourne (and including data provided by Dr Cairns), focused on the dingo-dog hybrids identified in previous research, concluding that the genetic signals marking these animals as hybrids originated thousands of years ago when dingo and dog first split. In fact, they concluded, dingo-dog mixing hardly ever happens—and, when it does, the descendants rarely go on to have offspring of their own. Dingoes, in other words, have preferentially bred with dingoes for so long that they are now on a trajectory towards becoming an entirely new species.

The findings are not all that surprising. Escaped domestic dogs are unlikely to survive for long in the bush, and any that wander up to a healthy dingo pack are much more likely to be attacked than mated with. The irony of culling dingoes is that, by disrupting their social structures and crashing their populations, it may make desperate dingoes more likely to start mating with domestic dogs.

Despite the revelations, Australian state authorities and farmers have largely continued with culls. The Victoria state government, one of the few exceptions, now protects a genetically isolated population of dingoes in its north-west, shown by the recent studies to be at imminent risk of dying out, while still permitting lethal control of dingoes in its eastern region.

Compromises are possible. Non-lethal measures, such as electric fencing and guard dogs, could be deployed more widely. Researchers are also investigating chemical compounds in male dingo urine which could be used as a deterrent.

As the debate around dingo control continues, Dr Cairns is excited by a yet more powerful genetic technology: whole-genome sequencing. It allows scientists to look at the entire DNA sequence of an animal, rather than an array of different points. This could help researchers dig even deeper into dingoes’ identity and finally unearth the story of their origins. ■

That’s likely and there’s also another possible reason.

Sheet glass was originally made by drawing molten glass vertically through a die, which resulted in glass that was somewhat wavy in appearance and not uniformly thick. This product is known as “drawn sheet” glass and is considered to be a cheap and inferior product. It was also tricky to cut as the break did not always follow the scored line perfectly.

By contrast, sheet glass is now made by floating molten glass on a bed of molten metal and results in perfectly clear glass of a consistent thickness. This product is called “float glass” and is also referred to as “plate glass”. It is much easier to cut.

I spent several years working in the flat glass industry and was lucky enough to observe the float glass manufacturing process (“the river of glass”) at the Pilkingtons factory in Dandenong.

i like that

it would be interesting to see how something as fundamental as glass is produced

One step of the process that intrigued me was the cutting of the continuous flow of the finished product into factory run sized sheets (typically 3.66 x 2.44 metres).

The cutting wheel was offset at a particular oblique angle that, combined with the moving stream of glass, resulted in a perfectly square cut.

The breadth of experiences covered by posters on this forum always amazes me.

Kids excursions to these sort of places are wasted. Should be for adults.

National Geographic Lovers: Nature, Animals & Ancient History ·

Join

Hassan Mohamed · poedtnorSs3908 mil9yM6f9ficua0cA84: fua1fh3fug75c92t98 iM0 9 ·

A massive 35-mile crack has appeared in Ethiopia — a striking sign that Africa is slowly breaking apart and a new ocean is on the horizon.

Beneath the blistering heat of East Africa’s Afar region, a powerful geological shift is underway. The African continent is gradually splitting in a tectonic process that will eventually divide land and form a new ocean basin.

Thanks to modern satellite imagery and GPS tracking, scientists have been able to study the East African Rift System — a rare spot on Earth where three tectonic plates (the Nubian, Somali, and Arabian) are drifting away from one another.

Though the movement happens at a pace of just a few millimeters to centimeters per year, over millions of years, it’s paving the way for a monumental transformation. One of the most dramatic examples occurred in 2005, when a 35-mile fissure tore through Ethiopia’s desert — compressing centuries of tectonic activity into a matter of days. Experts believe that rising magma beneath the surface is building pressure and triggering these sudden shifts.

The Afar region offers scientists a rare look at how continents fracture and new oceanic crust begins to form. Within 5 to 10 million years, water from the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden is expected to rush in, creating a new ocean and reshaping Africa’s geography forever.

Credit:

Content adapted from geological research and satellite data on the East African Rift System. Created for educational purposes, shared via A Solo Traveller

[

Join

Ancient Whispers · nrpeSodost1 5h m69097:cm94Mcu0081y0 m5A1aafuuta4ct6 Mf020cut ·

Forget the Greek philosopher for a moment! A 3,700-year-old clay tablet, unearthed from the sands of ancient Mesopotamia, whispers a mathematical secret that predates Pythagoras by over a millennium, rewriting the history books of geometry. This unassuming artifact, known as IM 67118, stands as a testament to the sophisticated mathematical prowess of the Babylonians, revealing their deep understanding and application of the principle we now call the Pythagorean theorem long before Pythagoras was even born.

Dating back to approximately 1770 BCE, this remarkable tablet captures a Babylonian teacher’s lesson etched in cuneiform script onto wet clay. The inscription meticulously details the steps to calculate the diagonal of a rectangle. What’s truly astonishing is that the method employed is precisely what we recognize today as the Pythagorean theorem: $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$. Here, a and b represent the lengths of the rectangle’s sides, and c represents the length of its diagonal. This discovery definitively demonstrates that the Babylonians were not only familiar with this fundamental geometric relationship but were actively teaching and applying it in their mathematical practices during the Bronze Age, while Greece was still in its formative years.

Adding further weight to the Babylonians’ advanced mathematical knowledge is the even older Plimpton 322 tablet, estimated to be from around 1800 BCE. This tablet contains a carefully organized list of Pythagorean triples – sets of three positive integers that satisfy the Pythagorean theorem, such as the well-known 3-4-5. The systematic arrangement of these triples suggests that Plimpton 322 was likely more than just a collection of examples; it appears to have served as a sophisticated mathematical tool, perhaps even a textbook for advanced students exploring number theory and geometry.

Beyond this groundbreaking understanding of right-angled triangles, the Babylonians left another indelible mark on our modern world through their ingenious base-60 number system. This sexagesimal system, with its roots in ancient Sumer, might seem archaic, yet its influence persists in the very fabric of our daily lives. We still divide our hours into 60 minutes and our minutes into 60 seconds, a direct inheritance from Babylonian mathematical conventions. Similarly, the division of a circle into 360 degrees owes its origin to this ancient system. This lasting legacy underscores the profound and enduring impact of Babylonian intellectual achievements on the development of mathematics and its subsequent influence on our measurement of time and space.

Therefore, while Pythagoras is undoubtedly a pivotal figure in the history of mathematics, the Babylonian tablets serve as a powerful reminder that mathematical innovation flourished long before the classical Greek era. These ancient scribes, working with clay and cuneiform, had already unlocked fundamental geometric principles and established numerical systems that continue to shape our world, proving that the “Pythagorean” theorem was, in fact, an ancient Babylonian gem.

Does Pythagoras mean plagiarist in Babylonian ?