A guide to what’s in dispute in the South China Sea, which is just about everything really.

One of those above places in dispute… yeah, it’s hotting up.

As Australia works it way through China’s restrictions on imports of selected goods, there’s a start up in tit for tat with Canada and others .

After Canada followed suit with the US in imposing 100% tariffs on EVs, steel and aluminium, China opened anti-dumping procedures against Canadian canola and some chemicals. Whatever the decision, it will have a chilling affect on traders.

Same ■■■■ with different country

China’s Taiwan Nightmare Has Come True

Taiwan has undergone a seismic demographic and political transformation in recent decades—a transformation that virtually precludes pacific unification between Taiwan and China.

Imagine that. Constant bombast coupled with daily armed provocations is no way to endear yourself to audiences overseas. Or, as the Wall Street Journal put it recently, “China confronts a new political reality in Taiwan: no friends.” The Journal’s brief is compelling. Taiwan has undergone a seismic demographic and political transformation in recent decades—a transformation that virtually precludes pacific unification between Taiwan and China.

China’s Taiwan Challenge

If China enjoys no support among Taiwan’s political parties, there’s little prospect a China-friendly president will take up residence in the Presidential Office in Taipei following this month’s elections. Without a China-friendly president and legislature, China stands vanishingly little chance of achieving its paramount goal of gaining control of the island without fighting. It will have to deploy armed force, with all the hazards and costs warfare entails.

And Chinese Communist Party officialdom has no one to blame but itself for this sad state of affairs. Its diplomacy seems almost deliberately designed to drive away prospective friends and unite alliances and coalitions to defeat the party’s aims.

Admittedly, demographics is not China’s friend in the Taiwan Strait. As recently as twenty years ago, sentiment among islanders was roughly evenly divided between advocates of unification with the mainland and advocates of independence. At the extremes, around ten percent favored immediate unification, and another ten percent favored immediate independence. The middle eighty percent seemed more or less content with the cross-strait status quo, voicing support for unification or independence but on no particular timetable. Moderates were happy to kick the can down the road indefinitely rather than undergo the upheaval from drastic political change.

Since then, things have deteriorated from Beijing’s standpoint. It’s an iron law that generational change happens as older generations pass from this earth and that a society’s attitudes may change as youthful generations molded by different formative experiences take charge.

Since the turn of the century, the proportion of “mainlanders” who fled to Taiwan in the wake of defeat in the Chinese Civil War and who define themselves primarily as Chinese has shriveled to under three percent of the populace, according to the Journal. That’s not a meaningful constituency in favor of a cross-strait union. No one caters to three percent of the electorate.

Youthful islanders define themselves chiefly as Taiwanese, not Chinese. They display little affinity—let alone allegiance—to China. Unsurprisingly, then, none of the three parties vying for the island’s presidency has made unification a major theme while barnstorming for votes. Just the opposite, in fact. Even the Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT, which has cozied up to Beijing in the past, has muffled any advocacy of closer cross-strait ties into near-silence. That’s how electoral politicking works.

You would think even communists would grasp the basic vagaries of democratic politics. You would be wrong. Indeed, China’s conduct vis-à-vis Taiwan amounts to diplomatic malpractice. It’s a self-defeating policy, and foreseeably so. Beijing’s failure to woo the islanders is part of its larger turn away from “soft power” toward raw coercion and intimidation. It wants to overawe rather than allure.

For Joseph Nye, who coined the phrase, soft power is a power of civilizational attraction. It helps the leaders of a society that’s attractive to others get their way when negotiating with foreign leaders. Soft power encourages others to want what you want.

For America, talismans of soft power include the United States’ relative openness to outsiders, founding documents such as the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, and pop-culture products such as movies and music. China can appeal to its long history, impressive art and architecture, and venerated historical figures like the philosopher Confucius or the Ming Dynasty diplomat-admiral Zheng He. Beijing used to understand all of this. Not so long ago, Chinese emissaries pursued a soft-power offensive, a.k.a. “charm offensive,” toward China’s Asian neighbors. And they premised their outreach on Zheng He’s exploits while voyaging in maritime Asia during the fifteenth century.

Zheng He commanded the Ming “treasure fleet,” then the world’s largest, most technologically advanced navy, during a series of expeditions to Southeast and South Asia. The voyages weren’t entirely nonviolent in nature—the fleet battled piracy near Malacca, for example—but they were not voyages of territorial conquest. That Zheng He abstained from conquest cast the keystone for Communist China’s charm offensive six centuries later.

Beijing invoked Zheng He’s journeys to portray China in a positive light compared to predatory Western empires that trampled Asian sovereignty for half a millennium. Spokesmen contended that China’s true, ineluctable, anti-imperial nature had manifested itself through the treasure voyages. The narrative reassured Asians that they could trust a strong maritime China not to wrest territory from them. Here’s the thing, though: when you sketch a narrative that supposedly depicts your society’s intrinsic culture, you set a standard for your future conduct. Foreign audiences will hold you to that standard. They will notice if you deviate from it. Future soft-power appeals will fall flat if you do.

False storylines will do that.

There were worrisome signs even during the heyday of China’s charm offensive. Beijing enacted an “Anti-Secession Law” in 2005, vowing to use force against Taiwan should the island’s leadership move toward formal independence from the mainland. In 2009, the party leadership submitted a map to the United Nations claiming “indisputable sovereignty” over waters and landmasses within a “nine-dashed line” enclosing the vast majority of the South China Sea, including swathes of exclusive economic zones belonging to China’s neighbors. In 2012, it seized Scarborough Shoal, a feature deep within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. In 2013, it took to manufacturing artificial islands in the South China Sea. Etc.

So much for China’s claim to be an innately self-denying, innately trustworthy seafaring power. Bullying is now a daily routine for China’s navy, coast guard, and maritime militia. And Chinese soft power lies in the wreckage.

Not that Xi Jinping & Co. seem to care. They jettisoned a mode of diplomacy that offered promising results and directed Chinese representatives to comport themselves like jackasses toward foreign interlocutors. Jackass diplomacy is diametrically opposed to Zheng He diplomacy, which aimed at conciliating others. Nor has Beijing’s turnabout escaped notice in Asian and Western capitals. Its swerve to heavy-handed means alienates potential sources of support for Taiwan, fuels arms buildups in countries fearful of Chinese predations, and herds rival powers into hostile alliances, coalitions, and partnerships.

Why engage in behavior that seems consciously calculated to guarantee that China wins no friends? You have to think domineering conduct is engraved on Chinese habits of mind and deed and thus on Chinese political and strategic culture. If so, officialdom is acting on ingrained ways of thinking, feeling, and doing. Beijing is captive to longstanding and highhanded traditions. Party chieftains can’t help themselves.

Now, there’s a narrative that explains much about China’s past, present, and potentially future actions. Prepare accordingly.

Wong and Marles must speak up about Chinese incursions into Japan

4 Sep 2024|

China has recently made two provocative military incursions into Japanese territory in just a week, with a surveillance plane breaching airspace on 26 August and a survey ship entering territorial waters on 31 August.

On 5 September, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Defence Minister Richard Marles will host their Japanese counterparts for 2+2 consultations. They should use the opportunity to call out China’s aggressive behaviour, rectifying Canberra’s tardiness and laying down a marker that such breaches of international rules will be met by a collective response.

We must not become desensitised to, nor casually dismiss, Beijing’s provocations. While Chinese survey ships and submarines have entered Japanese waters before, this was the first time that a Chinese military aircraft has violated Japan’s territorial airspace.

Unlike the disputed Senkaku Islands near Taiwan, where China sent a non-military plane in 2012, last week’s airspace violation took place in territory universally recognised as belonging to Japan, which should make it easier for Australia and other countries to condemn Beijing’s actions unreservedly.

These latest incursions follow two violations of Japanese airspace by Russian helicopters since 2022—seemingly warnings over Tokyo’s support for Ukraine. An ineffective response, including from Japan’s partners, might embolden Beijing and Moscow to push their ‘no limits’ partnership even further, such as taking greater risks in the joint military exercises that they already conduct around Japan.

Beijing’s transgressions were no accident, as the publicly available flight plan of the People’s Liberation Army aircraft showed. This fits a pattern of dangerous brinkmanship by Beijing, which included the sonar targeting of Australian navy divers from HMAS Toowoomba in 2023 and the release of flares near an Australian navy helicopter in May this year. Such acts are intended to test the resolve and solidarity of Beijing’s democratic rivals, as well as the response times of their armed forces.

As ever, Beijing’s motivations are murky. It’s possible that the Chinese leadership wanted to influence the selection process for a new Japanese prime minister later this month. Or they might have been aiming to dissuade Japan from hosting the armed forces of democratic partners, as occurred last month when an Italian aircraft carrier docked near Tokyo—part of an Indo-Pacific deployment that included the Pitch Black military exercises in Australia.

Alternatively, Beijing might be picking on Japan as part of a grander regional plan. Around the same time as these incursions, Chinese coast guard ships rammed a Philippines counterpart in the South China Sea, and the leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum were strong-armed into removing a reference to Taiwan from their joint communique.

Whatever its overarching strategy, such incursions reflect Beijing’s relentless tactical probing, which is designed to test the military, political and diplomatic responsiveness of its rivals.

Despite the leadership transition, Tokyo has made clear that China’s breaches of Japanese sovereignty are unacceptable. Australian ministers must offer their support, just as they would expect from Japan and other close partners were our territorial integrity challenged so brazenly.

Beijing will claim that this is a bilateral issue with Tokyo, best handled through quiet diplomacy behind closed doors, and that any other country that shows an interest is interfering. Sadly, Beijing’s narrative has gained traction in Southeast Asia, where elites misidentify the Philippines’ alliances and broadcasting of China’s maritime aggression on social media as the problem rather than the remedy.

Setting aside sovereignty disputes, members of the Association of South East Asian Nations should be able to agree that China’s use of force against the Philippines violates international rules, including ASEAN’s declaration on the conduct of parties in the South China Sea, which Beijing has signed. A strong statement by Southeast Asian countries would be a powerful rebuke of Beijing and an affirmation that ASEAN stands by its principles.

Transparency is not a magic wand, but evidence shows that it helps counter Chinese bullying. For instance, the Chinese navy does not appear to have locked its radars onto Japanese targets since it was called out for doing so in 2013 by Shinzo Abe, the Japanese prime minister at the time, and other ministers.

But speaking out is most effective in company, supported by hard power. The joint statement on maritime cooperative activity between Australia, Japan, the Philippines and the US in April this year met this bar. While its language was careful, Beijing’s unlawful conduct in the South China Sea was clearly the target, and the rhetoric was backed by joint exercises and other initiatives. Such collective actions communicate that deterrence goes deeper than the US’ bilateral security treaties or the whim of whoever occupies the White House.

Solidarity is especially important between Japan and Australia, which have become allies in all but name, including borrowing language from the ANZUS treaty in an upgraded security agreement in 2022. Beyond their bilateral reciprocal access agreement that facilitates military exchanges, Australia and Japan also cooperate trilaterally with their US ally on priorities like networked air and missile defence. And Japan is front of the queue for contributing to AUKUS Pillar 2 advanced capabilities.

Therefore, it is vital that Australian and Japanese ministers unreservedly support each other when they stand side-by-side before the media tomorrow. A genuine partnership needs a common language on regional threats, from Beijing’s coercion to sabre-rattling by Pyongyang and Moscow. Good news stories about practical cooperation and the bonds between our nations matter, but effective deterrence also requires the naming and shaming of bad actors.

Turkey had the right idea!

Leaders | Going dark

The real problem with China’s economy

The country risks making some of the mistakes the Soviet Union did

image: Getty Images/Carl Godfrey

Sep 5th 2024

China’S giant economy faces an equally giant crisis of confidence—and a growing deficit of accurate information is only making things worse. Even as the country wrestles with a property crash, the services sector slowed by one measure in August. Consumers are fed up. Multinational firms are taking money out of China at a record pace and foreign China-watchers are trimming their forecasts for economic growth.

The gloom reflects real problems, from half-built houses to bad debts. But it also reflects growing mistrust of information about China. The government is widely believed to be massaging data, suppressing sensitive facts and sometimes offering delusional prescriptions for the economy. This void feeds on itself: the more fragile the economy is, the more knowledge is suppressed and the more nerves fray. This is not just a cyclical problem of confidence. By backtracking on the decades-long policy of partially liberalising the flow of information, China will find it harder to complete its ambition of restructuring the economy around new industries. Like the Soviet Union, it risks instead becoming an example of how autocratic rule is not just illiberal but also inefficient.

- The Chinese authorities are concealing the state of the economy

- China is suffering from a crisis of confidence

The tightening of censorship under President Xi Jinping is well known. Social-media accounts are ever more strictly policed. Officials are warier of candid debate with outsiders. Scholars fear they are watched and business people mouth Communist Party slogans. Less familiar is the parallel disappearance of technical data, especially if it is awkward or embarrassing for the party. Figures for youth unemployment, a huge problem, have been “improved and optimised”—and lowered. Balance-of-payments statistics have become so murky that even America’s Treasury is baffled. On August 19th stock exchanges stopped publishing daily numbers on dwindling foreign-investment inflows. As the economic dashboard dims, the private sector is finding it harder to make good decisions. Officials probably are, too.

To understand the significance of this shift, look back to the mid-20th century. Witnessing the totalitarianism of the 1930s and 1940s, liberal thinkers such as Karl Popper and Friedrich Hayek argued that political freedom and economic success go hand in hand: decentralised power and information prevent tyranny and allow millions of firms and consumers to make better decisions and live better lives. The collapse of the Soviet Union proved them right. In order to maintain political dominance, its rulers ruthlessly controlled information. But that required brutal repression, starved the economy of price signals and created an edifice of lies. By the end, even the Soviet leadership was deprived of an accurate picture.

As China grew more open in the late 1990s and 2000s, its leaders hoped to maintain control while avoiding the Soviet Union’s mistakes. For many years they allowed technical information in business, the economy and science to flow far more freely. Think of Chinese firms with listed share prices disclosing information to investors in New York, or scientists sharing new research with groups abroad. Technology seemed to offer a more surgical way to censor mass opinion. The internet was intensively policed, but it was not banned.

China’s top leadership also redoubled its efforts to know what was going on. For decades, it has run a system known as neican, or internal reference, in which journalists and officials compile private reports. During the Tiananmen Square protests, for example, the leadership received constant updates. Techno-utopian party loyalists reckoned that big data and artificial intelligence could improve this system, creating a high-tech panopticon for the supreme leader that would allow the kind of enlightened central planning the Soviets failed at.

It is this vision of a partially open, hyper-efficient China that is now in doubt. Amid a widening culture of fear and a determination to put national security before the economy, the party has proved unable or unwilling to limit the scope of its interference in information flows. Monetary-policy documents and the annual reports of China’s mega-banks now invoke Xi Jinping Thought. Deadly-dull foreign management consultants are treated as spies. This is happening despite the fact that China’s increasingly sophisticated economy requires more fluid and complex decision-making.

An obvious result is the retreat of individual liberty. In a reversal of its partial opening, China has become a more repressive place. Many Chinese still have liberal views and enjoy debate but stick to private gatherings. They present no immediate danger to the party.

The information void’s other effects pose more of a threat. As price signals dim, the allocation of capital is getting harder. This comes at a delicate moment. As its workforce shrinks, China must rely more on boosting productivity to grow. That is all about using resources well. The country needs to pivot away from cheap credit and construction to innovative industries and supplying consumers. That is why capital spending is pouring into electric vehicles, semiconductors and more. Yet if investment is based on erroneous calculations of demand and supply, or if data on subsidies and profits are suppressed, then the odds of a successful transition are low.

China’s admirers might retort that the country’s key decision-makers still have good information with which to steer the economy. But nobody really knows what data and reports Mr Xi sees. Moreover, as the public square empties it is a good bet that the flow of private information is becoming more distorted and less subject to scrutiny. No one wants to sign a memo that says one of Mr Xi’s signature policies is failing.

After the horrors of the mid-20th century, liberal thinkers understood that free-flowing information improves decision-making, reduces the odds of grave mistakes and makes it easier for societies to evolve. But when information is suppressed, it turns into a source of power and corruption. Over time, the distortions and inefficiencies mount. China has big opportunities but it also faces immense problems. A fully informed citizenry, private sector and government would be far better equipped to take on the challenges ahead. ■

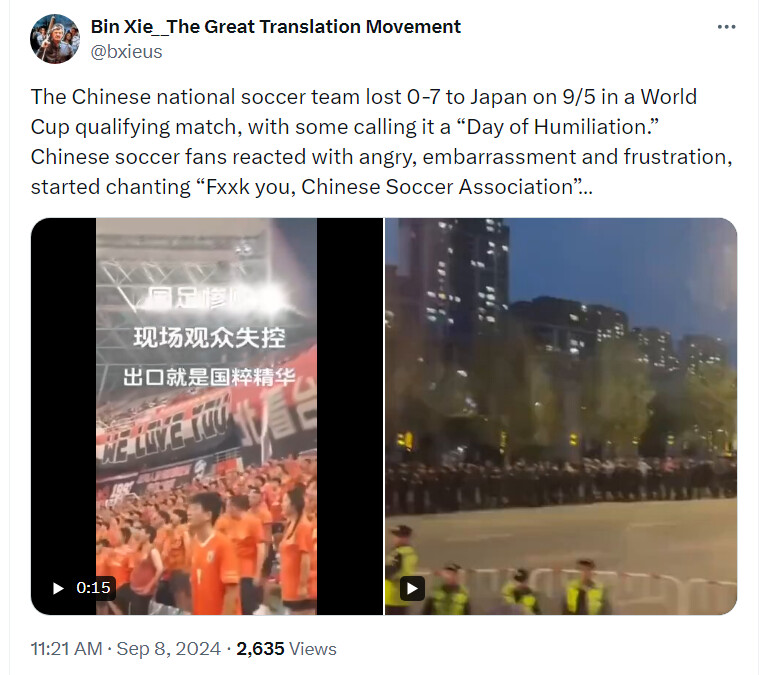

Not long after l arrived in China, a new sports minister came to power. He vowed to rid football of match fixing within a few/3 years, or else he would resign. As time went on he stuck to his word, and resigned. Football match fixing was and probably still is endemic.

They should be happy they haven’t had FIFA use them as scapegoats for other winning countries’ illegal drug taking.

He is far more honest than the AFL fat cat executives then.

Then again the guy who got China’s fast train system up and running was gaoled for corruption.

What is the story behind that?

China’s fast train system is just unbelievable in what it has achieved. And on so many levels: the engineering is incredible, the associated inventions are amazing, the societal benefits are amazing. And it exceeds the efforts of the rest of the world by orders of magnitude.

64 million rmb in bribes taken

His brother who was a given a decent gig in the ministry had amassed US$ 50 million in cash and 374 properties before being arrested

So basically took the P155

China’s rise in Southeast Asia is bringing in a golden age for Australia

Disquiet about Beijing’s growing presence

is motivating countries across the region

to seek deeper cooperation with Canberra.

Few close observers of Southeast Asia would dispute the claim that China’s influence across the region is growing. Beijing’s assiduous diplomacy and the promise of future economic rewards are pulling most of the region closer in. At the same time, Washington’s approaches, including economic protectionism, support for Israel over its war on Hamas, and continued diplomatic inattention, are pushing countries away.

As worrying as this picture is to Canberra, it is paradoxically creating a new golden age in Australia’s ties with the region. Because as China’s influence grows, so too do anxieties about its presence, even in countries such as Thailand, Cambodia and Malaysia, that have largely not seen China as a threat over the past two decades.

This disquiet about China’s growing presence is in turn motivating individuals and groups from across the region to seek deeper cooperation with Australia. All countries want more economic investment and presence by Australian businesses. The Malaysian and Indonesian defence establishments both want more cooperation with Australia, as demonstrated by the recent signing of a defence cooperation agreement between Canberra and Jakarta. Cambodia’s new generation of leaders is reaching out. Australia’s partnerships with Singapore and Vietnam are flourishing.

Some will point to this record as evidence that countries in the region are still “hedging” and avoiding alignment with any partner. But the better interpretation is that they are seeking deeper partnership with Australia not to avoid alignment, but because they see alignment as inevitable. There is simply no evidence for the proposition that any country in Southeast Asia, except for the Philippines and to a lesser extent Vietnam and Singapore, is willing to incur any costs from China in the interest of remaining non-aligned. Partnering with Australia (or the United States or Japan) will sit alongside, rather than lessen ties with China.

This distinction between avoiding alignment and managing the consequences of alignment might sound abstract. After all, if countries want to work with us, who cares why?

Partnering with Australia might be the geopolitical equivalent of the “lipstick effect” – a theory that cash-strapped consumers during tough economic times are likely to splurge on small affordable luxuries like makeup or cosmetics.

One reason to care is that unless we understand why countries are working with us, we risk misinterpreting the impact of such cooperation. For example, if we believe that Malaysia seeks closer defence cooperation with Australia to avoid aligning with China , then it follows that such cooperation can have an effect in shaping Malaysia’s overall strategic outlook. If, on the other hand, we judge that the Malaysian defence officials seek closer ties with Australia because they are anxious that it is aligning with China then the wider effect of such cooperation will be limited. Relationships with the Malaysian Armed Forces may be stronger and friendlier, the two countries may carry out more sophisticated combined exercises, but Australia will not be able to increase – or could even still lose – access, basing and overflight rights.

Likewise in the case of Cambodia. If we assess that Hun Manet and his new generation of technocratic leaders are seeking to avoid aligning with China then it follows that investing more in the relationship will yield a dividend, with the country more willing to resist pressure from China in regional forums or to prevent China from gaining exclusive access to Ream Naval base. If, on the other hand, Hun Manet and his coterie are merely belatedly responding to the realisation that Cambodia has become too dependent on China and would like to retain other partners in the mix, then whatever resources Australia might bring to bear will have little effect in preventing Phnom Penh from becoming a proxy for Beijing.

This isn’t to say we should turn off the tap. Most of what we do is in our own interests. Encouraging Australian businesses to invest more in the region isn’t just about responding to a demand signal from political leaders, but about seizing an economic opportunity. Political and defence cooperation with countries in our own region promotes a range of Australian interests, such as countering transnational crime, maintaining situational awareness of the region’s maritime domain, and collaborating on shared regional issues.

In terms of the broader geopolitical dynamic in the region, however, partnering with Australia might be the geopolitical equivalent of the “lipstick effect” – a theory that cash-strapped consumers during tough economic times are likely to splurge on small affordable luxuries like makeup or cosmetics. When China’s influence is rising, cooperation with a smaller and capable partner such as Australia might help Southeast Asian countries feel less anxious, but it’s unlikely to change anything much.