How China’s big dreams will wipe out the world’s climate gains

By David Fickling

March 14, 2024 — 3.45pm

The data on carbon emissions in 2023 is only just in, but we can already predict where things will go this year.

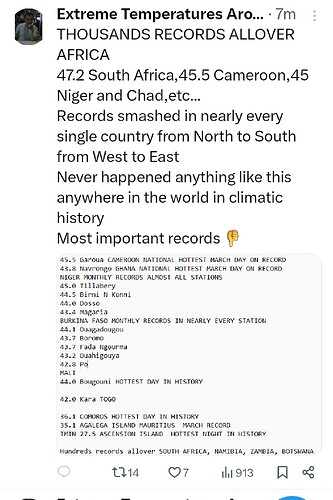

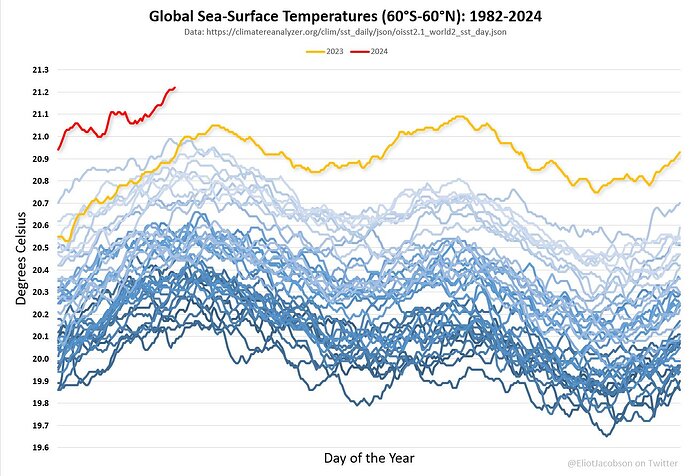

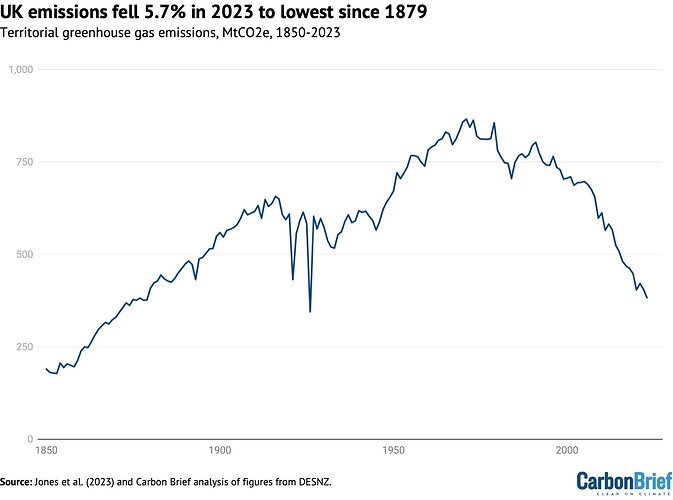

Global greenhouse pollution hit a new record and increased 1.1 per cent last year, the International Energy Agency reported last week. That was almost entirely a China story. Had the country held its carbon budget steady — or reduced it, in the manner of fellow high-income countries whose pollution is now at a 50-year low — then the world’s climate footprint would have shrunk by about 155 million metric tonnes, instead of growing by 410 million tonnes.

If you want to know how this year is shaping up, Beijing’s National People’s Congress provided a sneak peek. Its 5 per cent growth target announced doesn’t absolutely guarantee that global emissions will rise again in 2024. But it makes the path to avoiding that fate extraordinarily narrow.

That’s because a country’s greenhouse footprint can be boiled down to three factors: its economic growth, the energy intensity of that growth, and the carbon intensity of that energy. On all three, China performs dismally outside the norm — and the dirigiste policymaking typified by the NPC is the major culprit.

One way of looking at the nexus between pollution and economic growth is to ask how many tonnes of greenhouse gases it takes to produce a million dollars of economic output. Despite decades of gradual improvement, that figure is about 462 tonnes in China — close to double the 246 tonnes in the US and almost four times the 137 tonnes in the European Union.

Global greenhouse pollution hit a new record and increased 1.1 per cent last year.Credit: AP

Such a downbeat picture might seem surprising when set against the fact that China installed about three-fifths of all wind power and roughly the same share of solar globally last year. The clean energy generated by that equipment is a formidable brake on the country’s emissions — but it’s not strong enough to overcome the pull of the GDP growth target, especially not when the manufacture of metals and glass for all that new clean technology is a major contributor to China’s growing carbon footprint.

The fundamental problem is one of economic structure. In most countries, especially relatively affluent ones like China, GDP growth precedes increased energy consumption.The government and central bank set the basic rules of supply and demand, economic activity responds organically, and energy consumption and a GDP number are the result.

China appears to do things in the opposite fashion: the NPC sets a GDP and energy consumption goal, and provincial officials shape activity to produce the desired outcome. Polluting heavy industry is easy to control, so it’s relied on as a tool of demand management in the same way that other countries rely on central bank interest rates.

Beijing’s most senior officials have set great store by their plans to make their country not just wealthy, but clean and sustainable — “building a Beautiful China” and encouraging “harmony between human and nature”, to quote official media’s characterisation of Xi’s remarks at an internal conference last year.

It looks increasingly likely it will fall well short of those ambitions, as the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, a climate think tank, argued last month. Beijing’s insistence that it’s focused on achieving results around climate, while other governments make do with meaningless talk, looks more hollow with each passing year. A nation that can’t rein in its addiction to carbon can’t be trusted as a climate leader.

Bloomberg