The West Doesn’t Want Ukraine To Lose But Isn’t Ready For It To Win, Says Russia Policy Expert

October 04, 2024 05:41 GMT

A Ukrainian soldier fires at Russian positions using an American M777 howitzer near the front line of the Donetsk region. (file

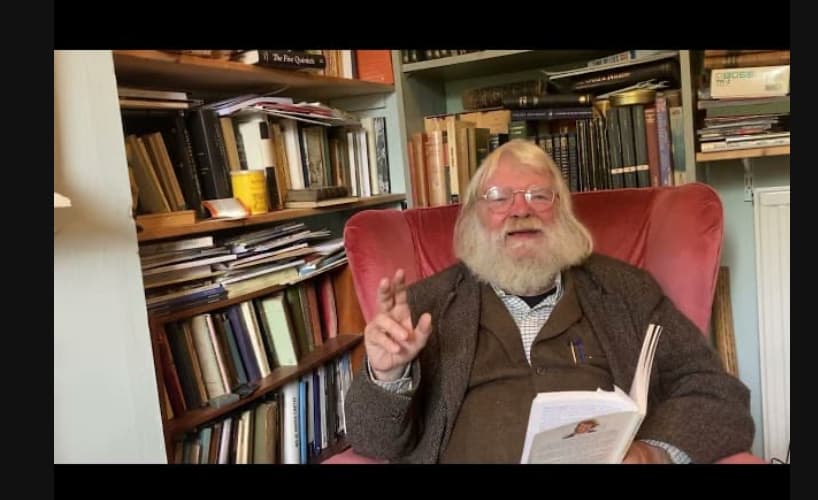

A leading expert on Russian foreign policy, James Nixey heads the Russia and Eurasia Program at Chatham House, a London-based research institute. In a recent interview with RFE/RL’s Georgian Service, Nixey, whose research focuses on the relationships between Russia and the other post-Soviet states, says he doesn’t think the Ukraine war will become “frozen,” given how much Russia has “gone all in” and how “so many have died” on the Ukrainian side.

RFE/RL: Is a victory for Ukraine still on the cards? What does it look like?

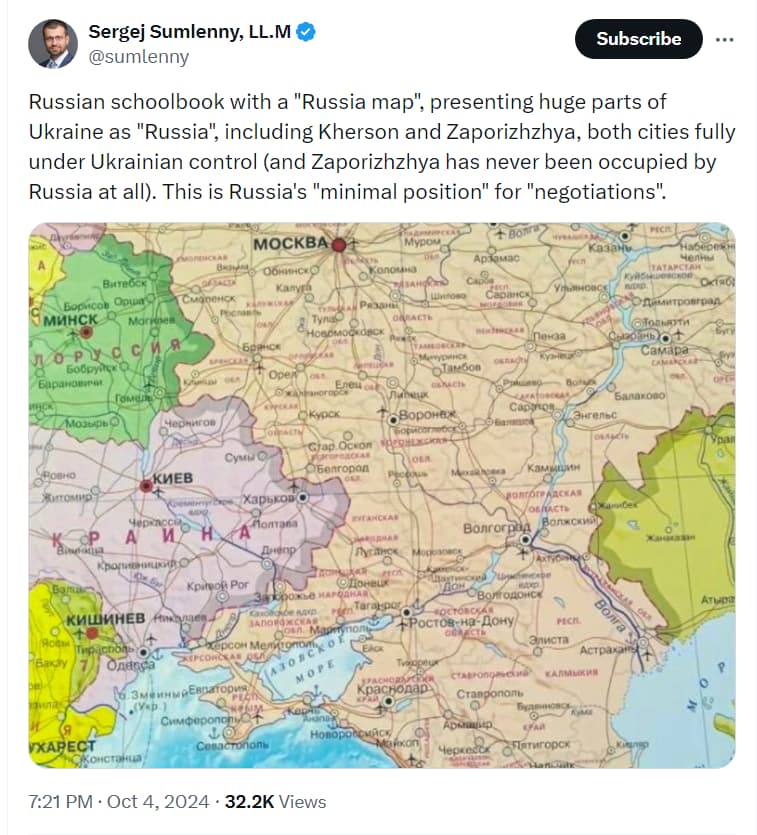

James Nixey: Ukraine’s victory is still pretty much what’s in [Ukrainian President Volodymyr] Zelenskiy’s 10-point [peace] plan, which is the maximalist objective, the all-you-want-for-Christmas: It is the withdrawal of Russian soldiers to pre-2014 (when Russia seized Crimea and began backing separatists in Donbas) lines and reparations and judicial reckoning.

Of course, I am often told, ‘But James, that’s not realistic. James, you’re being idealistic. James, surely, you’ve got to meet the Russians somewhere.’ And I don’t know that that’s necessarily true. It might be true.

RFE/RL: About meeting the Russians somewhere?

Nixey: Yes. It might be true, because analytically I can accept any proposition of any outcome… But because this war is not over, because it could go [in] any direction, because it’s always all-to-play-for, because it’s on a knife edge, I don’t understand why people say it is not advisable or desirable or realistic to go for maximalist objectives.

Of course, it is possible that Ukraine will be completely defeated [on the battlefield], but even then I find it quite hard to imagine a Ukraine which is totally subdued, because even if they lose officially, then there would be continual guerrilla warfare, continual jabs at an enemy.

By contrast, I can at least imagine what a Russian implosion [might look like], whether that’s on the front line going toward Moscow, whether it’s centered in Moscow, whether it goes through the regions…[as] some form of snowball. I’m not saying it will happen. I can’t be a predictor of the future, and we shouldn’t try it. But it does seem Russia is a little bit soft.

We shouldn’t underestimate how difficult this should be for Russia to fight this war. Can you imagine what a ■■■■ show it must be in the Kremlin trying to fight this war?.. And, of course, we should be making it harder and harder.

RFE/RL: Are there any smaller victories to be talked about as an eventual outcome of this war? Not the maximalist victory but something more compromise-based – what would that look like?

Nixey: You’re quite right to ask it, but [asking that] implies some form of concession to the Russian narrative… Do we give a piece of land? Do we give up neutrality? Almost anything, beyond the Kursk region (a Russian region bordering Ukraine) is a very difficult thing to accept. It is really hard to imagine how Ukraine would be satisfied with any concession.

If you examine [these options] one by one, territorially – Crimea even – I don’t see how that’s ever going to really work. I know it could be in a frozen state, like it was between 2014 and 2022, more or less. But we clearly know anyway that Crimea alone is not enough for Russia. So, it almost doesn’t make sense talking about it.

If you take the question of neutrality or non-NATO membership, non-EU membership even, it overtly accepts a Russian sphere of influence. And, honestly, I have no faith in Western politicians.

"…the Biden administration and probably the Harris administration – if there is one – are not comfortable with a Russian defeat. They are genuinely worried that it would create anarchy, loose nukes, spillover, civil war, things they can’t control.

RFE/RL: What would be something Ukraine could conceivably settle for and still consider itself victorious?

Nixey: Nobody wants to be in the position where they are making moral compromises, where we let Russia walk away from it. [It] doesn’t sit well…does it?

Of course, there still would be some push [for justice]; you can’t rescind [the International Criminal Court] arrest warrant. It still would be there, but that’s it.

RFE/RL: Putin could still go to Mongolia, though. (Russian President Vladimir Putin recently visited Ulan Bator, a signatory to the International Criminal Court.)

Nixey: Exactly. It is astonishing, the naivete, of many Western commentators and experts, who say: This is an affront to international justice. Did anybody seriously expect Ulan Bator to arrest Vladimir Putin? Then you’re not living in the real world. That’s bizarre. The affront to international law is not Mongolia, it’s Russia.

RFE/RL: If we are going down this rabbit hole, let’s dig in deeper: Is there is a nondefeat scenario for Ukraine, where [Ukraine cannot] claim victory in any way, shape, or form, and neither can Russia? Where does that leave us? Frozen conflict?

Nixey: It doesn’t strike me as a frozen conflict situation. It’s gone too far. If you think about the war in 2008 (when Russian forces invaded Georgia), which was more horrific for you than it was for me, but I still remember being horrified by it.

It was five days, and it was, I’m sorry to say this, and I mean no offense, but it was a clear victory. Obviously, in a situation where you have quite a clear ending over a short period of time, then that leads to a frozen agreement. Georgia and Russia don’t agree… [The pro-Russian breakaway region of] Transdniester, Moldova’s too weak to do anything about it.

The war in Ukraine is an absolutely…unique situation. And, unfortunately, there’s no going back from it. 2014? Crimea, the Donbas – that was freezable. I find it hard to see people…going on with their lives in this situation, when so many have died, when it’s been such a shakeup of a system, when Russia’s gone all in, doubled down. It just makes freezing harder. Because it was hotter, it’s harder to freeze, I suppose.

I just fail to imagine a situation whereby Ukraine is totally subdued and relatively happy with the status quo as it is right now. I might be lacking imagination, but it’s not easy to see how that could play out satisfactorily. And it would be politically risky for Zelenskiy. If he were to submit to nearly all of the Russian narrative, that would be the end of Zelenskiy.

RFE/RL: Does the West have any sort of endgame vision for Ukraine? Does it subscribe to any one scenario and is willing to pursue it?

Nixey: As the Russians say: “zhelatelno by” – if only. That’s a wish, right? The wish is that somehow the West, [the] collective West, gets its act together and doubles down, has a real plan, [an] operational conclusion that it needs to win this, to help on all sorts of other problems, because it really would help on all sorts of other problems, not just China and so on. It doesn’t, and this is what my problem is. What we do is we do just enough; we drip feed, we don’t do badly, we’re not awful, but we’re just not good enough.

RFE/RL: Much like [English soccer team] Tottenham Hotspur, then?

Nixey: Ha ha, yes. That is true. There are sporting analogies. I don’t think the West has done a particularly awful job. I just don’t think it’s done a good enough job. The scale of the challenge is so much harder.

I get it’s hard. Inevitably, this is life… You’re never gonna get 100 percent cohesiveness… It’s just not possible. It is a family, but it’s a family with problem children. It’s a family with disruption and disruptors, some of whom are working for the other side effectively. But it’s still kind of a family. And so we always ask the question: Can we get this together?

It is ultimately true that the [U.S. President Joe] Biden administration and probably the [Democratic Party presidential candidate Kamala] Harris administration – if there is one – are not comfortable with a Russian defeat. They are genuinely worried that it would create anarchy, loose nukes, spillover, civil war, things they can’t control.

They want to be able to control this war. And a Russian defeat isn’t controllable, because none of us, fair enough, knows how that will play out.

I think that’s wrong in all sorts of ways, because frankly we’re already in my worst-case scenario, with the potential to take over Ukraine. But I think the truth – the real dirty uncomfortable reality – is that Ukraine can kind of be sacrificed if it means something approaching the old world order can be maintained.

I’m not suggesting they want to sacrifice Ukraine, they don’t; they’re not the devil, but they’re not the angel either. So the problem is we sort of have the worst of both worlds, an uncomfortable situation whereby you actually don’t have a frozen conflict but a protracted conflict because we don’t want to let it go, we don’t want to win, we don’t want to lose. That leads to paralysis.

RFE/RL: If a Russian defeat is not manageable and a Ukrainian defeat is also not manageable and desirable, what is manageable?

Nixey: What appears to be manageable is the new normal whereby you have a hot war, amazingly, which is apparently containable, with no spillover; it isn’t extended into Moldova or [the] Baltic states, or Georgia even.

It is funny, isn’t it, how comfortable policymakers are with here and now, because it’s the existence that they are living in and how uncomfortable they are with almost any change. Even [former U.K. Prime Minister Margaret] Thatcher didn’t want the unification of Germany. We know this from the records, because she didn’t understand or know how it would play out. To you, it looks completely obvious, but that’s hindsight, and she was pretty good on Cold War issues, but that’s the point.

It just goes to show how policymakers don’t want to reach for a substantive change. They are uncomfortable with the idea of anything that could shake up their little world. And that unfortunately creates the paralysis, the unhappiness, and the protraction of the situation.

Foreign policy expert James Nixey

There is a problem at the top, a lack of leadership with people who do not think like the president of Estonia or the president of Finland, or whatever, because they are much more concerned with the global status quo. They don’t see the risks from history and from [the] present that these countries on the front line do. There’s a totally different mentality. If you are living in Lisbon, and if you’re living in Tallinn, of course, you see different pictures. I do get that, just unfortunately we shouldn’t be listening to Lisbon as much as to Tallinn, but we do.

RFE/RL: To sum up, is the modus operandi then to wait, contain this war, and wait until Russia gets bored and decides to [leave?]

Nixey: Just on a microcosmic note, if you look at the F-16 [fighter jets] now delivered [to Ukraine], we do not still know what the restrictions on their use really are, especially while Russia is building airfields near the Ukrainian border.

Are the Americans giving permission to use that or not? It’s a small, important element of what I think your question is. When we look back on this, when we’re older, I would imagine that the Biden administration will not come out very well. History will not judge it well, just like it doesn’t judge [former U.S. President Barack] Obama well, unfortunately, because they’re good people, Biden’s a good person.

I suspect that if we have this continual arc of instability in whatever form, however this turns out but beyond [the] borders of Ukraine, then we will be able to point to this administration for its inability, albeit hamstrung by Congress etc., for its inability to exert its power.

[The United States] is a powerful country. It’s much more powerful than any other country in the world, including China itself. And it’s not willing to use it. Russia, by contrast, is not a powerful country, but it uses all the power it can possibly muster, and that’s a difference. Russia’s maximum extension of its power appears to be more than America’s minimal extension of its power.